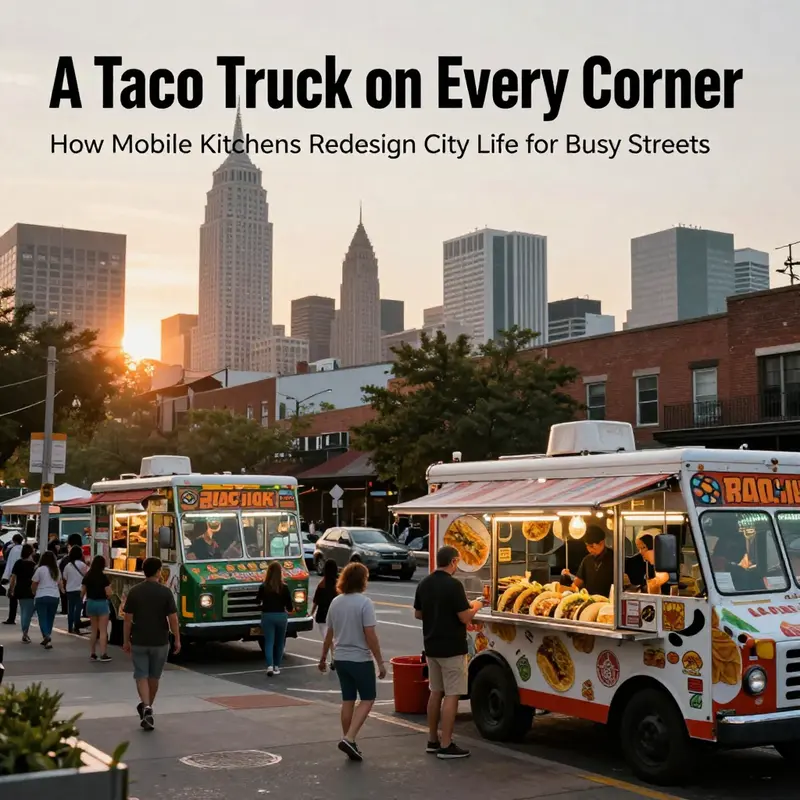

A taco truck on every corner isn’t just a quirky slogan; it’s a lens into how cities adapt to growing populations of commuters, outdoor enthusiasts, freelancers, and first-time buyers looking for practical, vibrant, and authentic meals. These mobile kitchens embody a flexible, low-overhead model that thrives on public space, neighborhood diversity, and the rhythms of urban life. In cities where parking spots and pedestrian lanes are precious, the mobility of a taco truck means meals travel to the people—often with a sense of place that fixed storefronts struggle to match. The concept raises important questions about how space is allocated, how local economies circulate, and how communities negotiate the benefits and challenges of informal enterprise. Across five chapters, we’ll unpack how a taco truck on every corner intersects with urban planning, entrepreneurship, regulation, cultural expression, and broader global policy. For urban commuters, the scene represents convenience and cultural flavor at street level; for outdoor enthusiasts, it’s fuel and social space during a hike, ride, or park visit; for small business owners and freelancers, it’s a pathway to entrepreneurship with modest risk and potential for community impact; and for first-time pickup buyers, it’s a case study in building a micro-business around mobility, opportunity, and adaptability. Each chapter builds toward a holistic understanding: this isn’t just about food; it’s about how cities evolve to welcome and regulate informal economies while preserving public safety, quality of life, and inclusive cultural landscapes.

A Taco Truck on Every Corner: Reimagining Public Space, Mobility, and Flavor in the Modern City

The refrain of a taco truck on every corner has moved from a slogan to a lens for urban life. It sits at the intersection of culture, economics, and the way cities allocate space in a changing public realm. In places like Los Angeles and Austin, the image is less about a single roaming vendor and more about a choreography of mobility, public space, and community resilience. The trucks themselves are portable micro architectures, open to the street with grills, steam, and bright signage, offering quick meals that carry history, family stories, and immigrant entrepreneurship. The phrase embodies opportunity and friction: opportunity to diversify diets, create entry points for small business, and animate public life; friction because every new truck shifts the balance of sidewalks, curbside parking, and street corners that already bear competing demands from pedestrians, cyclists, commuters, and local storefronts. The chapter that follows treats this image not as a dream of abundance but as a live debate about how urban planners, policymakers, and residents imagine the public realm in a city that prizes speed, accessibility, and cultural texture.

Urban planning at its core is about allocating space for competing uses while preserving the everyday rhythms that make a city livable. When a taco truck or a string of them appears, planners must consider sidewalks as more than walkways; they are platforms for social interaction, commerce, and neighborhood identity. Fixed storefronts once defined commercial districts by predictable boundaries. Mobile vendors blur those boundaries, occupying parts of streets, curb lanes, and plazas that were not zoned for year round commerce in the same way. This shift has driven a reevaluation of zoning models, rights of way, and the role of temporary activity in public space. The result is not a demolition of order but an invitation to design with flexibility. Cities have responded with mobile vendor programs, designated zones, and permitting regimes that aim to balance economic inclusion with safety, traffic management, and equitable access to public space. The practical mechanics of these policies—permits, hours of operation, location maps, and health standards—are not footnotes; they shape where a family can place its cart, how neighbors experience the street, and whether a community can see itself reflected in the culinary options that line a block.

In practice, the tension plays out in tangible ways. Vendors value mobility because it lowers barriers to entry. Start-up costs are modest, and the logistics of moving from one neighborhood to another allow for menu experimentation and responsiveness to changing demand. This agility contributes to a vibrant urban metabolism: new flavors, rotating menu items, and the ability to serve diverse neighborhoods without the overhead of a permanent brick-and-mortar site. Yet mobility complicates the predictable flow of pedestrians and vehicles. Sidewalks can become crowded when clever queuing interrupts the rhythm of a street, and curbside space used for loading or service may conflict with parking or transit accessibility. In response, jurisdictions have begun to carve out spaces that acknowledge the value of mobile food as part of the city’s fabric. Food truck parks or corridors concentrate activity in a controlled setting, reducing street-level conflicts while anchoring culinary activity in specific districts. They also enable coordinated waste management, shared utilities, and predictable enforcement, which benefits both vendors and residents.

The cultural meaning of a taco truck cannot be separated from its economic role. Taco trucks are often family-run operations that began as weekend or street-side ventures and evolved into community staples. They represent a pathway into the formal economy for people who arrive with experience, recipes, and networks from their countries of origin. The economic impact extends beyond the trucks themselves. As a mobile node in a local economy, a truck draws customers into neighboring stores, markets, and transit hubs. It can activate underused lanes and parking spaces, prompting ancillary activities as people linger for a meal and then shop, see a show, or catch a bus. The result is a more intricate urban ecosystem where the food vendor contributes to place making, resilience, and neighborhood cohesion. A 2016 analysis suggested that should taco trucks collectively employ three workers each, the sector could generate a substantial number of new jobs, highlighting the potential of mobile street vendors to contribute to broad-based employment within metropolitan areas. This is not merely about calories; it is about social mobility, skill development, and the symbolic power of small-scale enterprise within the citys public sphere.

However the growth of taco trucks also surfaces questions about equity and access. Who benefits when public space is commodified for commercial use, and who bears the costs when street activity encroaches on sidewalks, noise becomes a nuisance, or traffic patterns are altered? The literature on sociospatial dynamics emphasizes that the distribution of mobile vendors often mirrors historical immigration and settlement patterns, which means their presence on city streets also traces traces of cultural memory and adaptation. The public space question becomes a question of whose voices shape the rules of the street and how those rules are enforced. In this sense the debate transcends straightforward economic calculation. It encompasses perceptions of quality of life, fairness in enforcement, and the role of informal economies within regulated urban systems. When a city negotiates these dimensions with care, it can cultivate a street culture that is both efficient and inclusive, where street food is a venue for dialogue as well as nourishment.

A critical dimension in this negotiation is the design of regulatory frameworks that acknowledge the value of informal economies without surrendering the public realm to chaos. The Mobile Vendor Program in Los Angeles represents one template of adaptive planning: designated zones, permits, and operational hours that provide structure while embracing flexibility. The aim is not to eliminate informal activity but to integrate it into the fabric of the city in a way that is legible, accountable, and equitable. The official guidelines and maps offered by city agencies illustrate how planners translate abstract ideals—access, safety, inclusion—into practical steps. This approach aligns with a broader trend in urban policy that favors flexible, outcomes-based regulation over rigid, storefront-centered rules. The challenge remains to ensure that the benefits of mobile food circulation do not come at the cost of pedestrian safety, accessible sidewalks, or the rights of other street users. The balance is delicate, but the direction is clear: space is a shared resource that must be stewarded through thoughtful design, transparent processes, and ongoing dialogue with residents and vendors alike.

In this evolving landscape the chapter keeps returning to the central image: a taco truck on the street is both a culinary offer and a statement about who gets to occupy and shape public space. It is a reminder that cities are not static; they grow through transactions small and large—new recipes, new jobs, new rules. The path forward involves recognizing the strategic value of mobile vendors to cultural diversity and economic inclusion while simultaneously investing in planning tools that anticipate congestion, health standards, and equitable access. The idea of public space as a common good—shared, accessible, and adaptable—requires ongoing collaboration among planners, residents, and vendors. When people can see their own stories reflected in the street food that lines their blocks, the city becomes not only more flavorful but more just. The public realm benefits when policy and practice converge to celebrate mobility as a cultural and economic asset rather than as a nuisance to be managed away. As a result the urban landscape can host a vibrant mosaic of flavors that grow from the ground up, with street corners becoming stages for communal life rather than mere intersections of traffic.

For further exploration of how cities navigate these policy challenges while sustaining cultural vibrancy, see the broader academic discussion on engaging taco truck space in urban geography. As urban planners continue to rethink how public space is allocated, the model of a taco truck on every corner remains a useful lens for examining the compatibility of mobility, culture, and equitable access in the built environment. Sustainable practices of mobile food trucks can serve as a practical example of how communities integrate culinary mobility with planning goals, linking everyday nourishment to shared space and social inclusion. External resources and notes can provide additional context.

A Taco Truck on Every Corner: The Quiet Engine of Urban Economics and Local Entrepreneurship

Economic life, for many urban residents, is a tapestry woven from opportunity as much as supply. Taco trucks contribute to this tapestry by expanding dining options while lowering the entry price for a first-time business. Startups in this sector typically require far less upfront capital than a brick-and-mortar restaurant. A family can begin with a single cart, a simple griddle, and a handful of trusted recipes, then scale through experience, reputation, and occasional upgrades to equipment or space. This accessibility translates into a surprisingly broad labor-market effect: more people can test their entrepreneurial mettle, learn the basics of food safety, manage a small business, and gradually move toward formal arrangements if they choose. In immigrant communities, where formal pathways to traditional employment can be obstructed by documentation, language, or credential barriers, the taco truck model often serves as a doorway to economic participation. The operator learns to negotiate permits, source supplies, manage cash flow, and communicate with customers in a multilingual environment, building skills that have transferable value well beyond the cart lane. The proof is tangible in the way foot traffic concentrates around the truck’s location, spilling into nearby shops, coffee stands, and service providers. A busy corner becomes a micro-ecosystem: a plaza of exchange where meals, conversations, and small purchases reinforce each other. That circulation boosts not only the vendor’s revenue but the vitality of surrounding businesses, as customers linger longer, pluck a sandwich at a nearby counter, or stop to pick up ingredients for dinner. The ripple effects are measurable in reduced vacancy, in park and event economies that rely on portable food options, and in the way neighborhoods gain a reputation for affordability and character. When a street scene includes a taco truck, you are also watching a form of small-business incubation in action. The operator begins with a portable kitchen, tests a menu, learns customer preferences, and evolves with the rhythm of the city. In many stories, success rests on adaptability: a cart that pivots from traditional carnitas to a creative fusion—say, a taco with a nod to regional flavors elsewhere—can build a loyal following much faster than a fixed, slow-growth concept. The flexible labor structure of these operations often includes family members, friends, and neighbors who lend help during busy periods, contributing to a micro-economy that supports a broader spectrum of workers. The collective effect is a mosaic of small but cumulative gains, where each vendor adds to a city’s capacity to absorb shocks and to foster inclusive opportunity. We should note that policy contexts can either smooth or complicate these gains. Licensing regimes that are transparent, predictable, and scalable help vendors plan for growth and reduce the friction of day-to-day operations. When spaces are allocated through designated zones or parks—what urban planners sometimes call vending hubs—vendors can maximize visibility and customers can rely on consistent access to safe food and reliable service. In return, authorities benefit from clearer oversight, easier compliance checks, and better data on food-safety outcomes and tax-revenue channels. The economic argument is not merely about revenue: it is about creating a reliable linkage between informal effort and formal opportunity. A developmental regulatory approach—one that reduces barriers while maintaining hygiene and public space standards—can turn street vending into a conduit for resilience and inclusion, rather than a source of friction for neighbors and planners. The migration from informal to formal status is not a single leap but a continuum, where vendors gradually gain access to permits, official training, and microfinance options that seed expansion. In this sense, the taco truck economy becomes a living laboratory for inclusive growth, a space where entrepreneurship, labor-market participation, and urban policy intersect with real people, real kitchens, and real streets. The narrative around these trucks is also a story about consumer demand. People seek authenticity, affordability, and speed, but they also seek variety—fusion styles that blend local tastes with global influences and the comfort of a familiar, affordable meal. The demand side reinforces the supply side: trucks gravitate toward high-foot-traffic zones like transit corridors, event venues, and parks that host markets and festivals. In turn, nearby businesses gain when more pedestrians circulate, while event organizers and city staff learn to coordinate with mobile vendors to reduce crowding and improve safety. The result is a more dynamic urban food system that can adapt to seasonal surges, weekend crowds, and citywide celebrations without requiring costly capital investments from the municipal purse. For policy makers, the challenge lies in crafting a framework that recognizes the value of mobility and informal entrepreneurship while preserving the public health standards and city infrastructure that make urban life possible. This is where design matters: a set of well-structured licensing options, clearly defined vending zones, and supported pathways to formal finance can transform a lively street economy into a durable engine of local opportunity. It is also here that we see the potential for continuous innovation. Incubation models, mentorship networks, and partnerships with community organizations can help operators refine their menus, streamline operations, and adopt safer, more scalable practices. In this sense, the taco truck scene is not merely a culinary trend but a crucible for adaptive entrepreneurship, a space where cultural heritage meets market demand under the watchful eye of urban governance. As cities seek to balance livability with opportunity, the question shifts from whether taco trucks belong on the street to how to integrate them into a holistic urban-economy strategy. A sound approach emphasizes collaboration—vendors contributing to policy dialogue, planners sharing data about space and safety, and communities weighing in on what kind of street life they want to see. The result can be a more vibrant, inclusive urban economy where a taco truck on every corner becomes a symbol of local empowerment rather than a cultural afterthought. For readers seeking a practical entry point into sustainable practice and governance, a concrete starting place is recognizing that responsible mobility requires both imagination and infrastructure: the right permits, the right spaces, and the right support systems to ensure safety and reliability while preserving the spontaneity that makes street food so compelling. The intersection of street vending with urban policy is not a battlefield but a crossroads. When city administration, vendors, and neighborhood groups meet with shared aims—quality food, accessible employment, and well-ordered public space—the outcome is a more resilient economic ecosystem. In that sense, the phrase a taco truck on every corner becomes more than a throwaway line; it becomes a living blueprint for how communities can grow through accessible entrepreneurship, cultural vitality, and smart, inclusive governance. The road ahead invites continued experimentation and careful design, ensuring that the mobile kitchens of today lay the groundwork for a more equitable and vibrant urban future. In the spirit of practical improvement, consider the idea that sustainable practices for mobile food trucks are not merely about compliance but about elevating performance, reducing waste, and strengthening the trust between vendors and residents. Sustainable practices for mobile food trucks. These approaches—centered on hygiene, energy efficiency, waste management, and responsible sourcing—are emitters of change, helping vendors scale without sacrificing the urban values that communities hold dear. As cities continue to design streets that welcome entrepreneurship, the taco truck stands as a modest but powerful exemplar of how mobility, culture, and commerce can align to expand opportunity. External perspectives reinforce this view. A broader policy analysis of street vending highlights the need for licensing that is fair, spaces that are accessible, and a tax framework that aligns incentives for growth while maintaining public health and urban order. The broader literature suggests that with careful regulation and active vendor participation, street vending can contribute to local tax revenue, job creation, and the diversification of the urban economy. For a broader policy perspective on street vending and urban livelihoods, see the World Bank report on street vendors in the informal economy: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment/publication/street-vendors-in-the-informal-economy

A Corridor of Sizzle and Regulation: Reimagining Zoning for a Taco Truck Future

The image of a taco truck on every corner is a playful fantasy about late-night crowds and portable kitchens. It is a test case for how cities regulate space, health, and commerce in the same breath. When you walk a block in a city that treats street food as both culture and economy, you feel the tension between appetite and policy. The ubiquity imagined in the slogan depends less on culinary demand than on a regulatory climate that makes space for mobile vendors to operate, adapt, and grow. In this sense, the phrase points to a kind of urban choreography: trucks must move with the rhythm of sidewalks, curb space, and the ever-changing pattern of foot traffic, all while complying with a bundle of permits, health codes, and zoning rules. Regulators, health inspectors, and licensing offices become, in effect, the audience and the judges of this street food ballet. When the stage is clear, the performance is immediate, democratic, and diverse. When the stage is cluttered with red tape, the performance falters, and the vision of a taco truck-filled streetscape remains aspirational rather than actual.

Across major markets, the reality behind the popular image is that growth of mobile food vendors is largely constrained by a dense network of rules that govern where, when, and how these kitchens can operate. The core dynamic is not culinary appeal or entrepreneurial grit alone but the way cities structure space through permits, health and safety mandates, and location-specific restrictions. Take a city where parking is tightly regulated and curb space is treated as a scarce, high-demand resource. Here, getting a truck onto a busy corner means navigating a landscape of layered permissions: multiple permits that must align with vehicle standards, fire and sanitation codes that translate a kitchen-on-wheels into a compliant facility, and location policies that decide which streets are open to mobile vendors, and for how long. The cumulative effect is a gatekeeping system that can slow, complicate, or even stall expansion, regardless of how many people are hungry for a particular taco or how effectively a truck can innovate its menu.

In practice, the regulatory framework often acts as the most persistent bottleneck. Cities like Chicago have become notable for their stringent parking rules and the creation of designated operating zones that can constrain where a truck can park, for how long, and during which hours. Such constraints are recurring themes in the street-food regulatory conversation: the same rules meant to organize urban space can also deter the risk-taking that fuels entrepreneurship. And even when a city embraces mobile vendors in a policy sense, the specifics of health certifications, fire code compliance, and vehicle inspection regimes translate into real costs and time delays for operators who typically run lean operations with narrow profit margins. In this environment, a truck’s ability to respond quickly to demand hinges on the predictability and efficiency of permitting processes as much as on the truck’s ability to turn out excellent tortillas.

Another stubborn friction is misalignment between codes and the practical realities of mobile businesses. Municipal zoning often does not include clear, accessible categories for temporary or mobile food services. Some places lack a dedicated path for vehicles that are, in effect, small, rolling kiosks rather than fixed storefronts. The result is a patchwork where a strong concept can fail to scale because the legal framework does not accommodate the mobility that makes such ventures viable. A fierce issue in several cities is the prohibition on staying too long in a single location, which undercuts the advantage of building a local customer base near high-traffic corridors. In other instances, permit regimes are so costly or complex that entry becomes a barrier for aspiring operators, especially those from immigrant communities who bring authentic regional flavors but lack the bureaucratic networks to navigate arcane licensing ladders. The friction is not simply about dollars and time; it is about who gets to participate in the urban dining ecosystem and how inclusive the regulatory ecosystem actually is.

The regulatory picture also varies widely from one jurisdiction to the next. Some cities have modernized their approach, offering streamlined permit pathways, clearer guidelines for mobile vendors, and designated corridors or parks where trucks can operate with reasonable certainty. Others cling to older models that emphasize fixed, centralized dining spaces and treat curb space as a scarce, exclusively allocated resource for larger, brick-and-mortar establishments. The result is a mosaic of opportunities and obstacles that makes replicating success from one city to another risky. A truck that thrives in one neighborhood might struggle to find the same tempo in another if the regulatory tempo changes. This inconsistency complicates strategic planning for operators who aim to grow from weekend stand to city-wide network, and it also complicates policymakers who want a coherent, scalable framework that supports entrepreneurship while protecting public health and street safety.

Industry observers often point to regulatory constraints as the primary reason the utopian vision of ubiquitous taco trucks has not materialized at scale. A widely cited industry analysis from earlier years underscored that the friction arises from permitting hurdles and zoning limitations that prevent a simple, replicable expansion model. Even in cities renowned for their vibrant street food culture, the reality is narrow: only a small fraction of available permits are held by traditional taco trucks, signaling fierce competition and limited throughput in the permit system itself. This dynamic highlights a broader truth: the growth of mobile food vendors is deeply tied to policy design as much as to culinary talent or business acumen. Without reforms that align codes with the realities of mobile entrepreneurship, the dream of a taco truck dense city remains uneven, precarious, and unevenly distributed across neighborhoods.

What, then, would robust policy look like if it truly aimed to unleash mobile food entrepreneurship while preserving public health and urban livability? A core step would be to flatten the friction in permitting processes while preserving essential safety standards. This could involve creating clearly defined, mobile-friendly licensing tracks, reducing redundant inspections for vendors who meet ongoing compliance through a standardized set of checks, and establishing temporary or flexible zones that rotate with demand patterns rather than tying operators to a single, costly long-term permit. A complementary shift would be to recognize the unique advantages of mobility in urban dining: the ability to serve multiple neighborhoods, test menus quickly, respond to events, and distribute economic activity across corridors rather than concentrating it in a few districts. In addition, creating more food truck parks or designated corridors could concentrate activity in a way that improves oversight, reduces congestion, and invites the public to engage with a broader spectrum of flavors. Such designs would not just accommodate a higher number of trucks; they would cultivate a more inclusive, dynamic food landscape that mirrors the city’s cultural diversity and practical appetite for convenient, affordable meals.

The potential social and economic benefits are substantial. Mobile vendors tend to operate with relatively low overhead and flexible staffing, which can translate into meaningful employment opportunities and broader participation in the local economy. When zoning and permitting are predictable and navigable, operators can invest in better equipment, safer practices, and more consistent service, all of which contribute to a higher quality of life in surrounding neighborhoods. The street becomes not only a place to eat but a forum for cultural exchange, entrepreneurial learning, and neighborhood cohesion. The risk, of course, is that without thoughtful policy design, these benefits will be unevenly distributed, with some districts reaping most of the gains while others face ongoing barriers to entry. In that sense, the phrase “a taco truck on every corner” is a hopeful contour of equitable everyday access—an invitation to reimagine public space as a platform for diverse communities to feed each other, literally and figuratively, through policy that enables mobility rather than stifling it.

To connect the regulatory discussion to the broader urban planning discourse, consider the practical wisdom that emerges when we examine cross-regional experiences. For readers seeking a policy-oriented lens on how regulation shapes mobile food economies, there is a useful case study in the way cross-border trucking regulations influence compliance practices in adjacent industries. Surviving compliance best practices for cross-border trucking regulations offers transferable insights about how small operators can navigate complex rule sets, maintain safety standards, and build scalable processes in regulated environments. This guidance underscores a common thread: when rules are clear, predictable, and proportionate to risk, entrepreneurial activity flourishes rather than falters. The same logic applies to tacos on curb space—clear rules, predictable opportunities, and proportionate oversight can unlock a more vibrant, inclusive streetscape rather than suppressing it.

A Taco Truck on Every Corner: Cultural Identity in Motion, Community, and Inclusive Urban Life

On city blocks that once echoed mainly with the hiss of buses and the clatter of metal stairs, a new kind of street-level theater unfolds each evening. A taco truck arrives not as a single convenience but as a mobile forum where scent, memory, and negotiation intersect. The phrase a taco truck on every corner—long used as a playful caricature of abundance—has become a meaningful lens for examining how urban space, immigrant entrepreneurship, and cultural expression braid themselves into the daily life of a city. The image invites us to imagine not just more meals but more visibility for communities whose stories feed the city’s pace. In cities such as Austin, where food trucks have deep roots in local identity, the taco truck has evolved from weekend stand to community institution, a symbol of how mobility can translate heritage into everyday experience. Yet the chapter’s focus extends beyond appetite. It asks how a fleet of mobile kitchens shapes cultural identity, nurtures belonging, and tests the boundaries of inclusion in public space. Read through this lens, the street becomes a classroom, a marketplace, and a commons where memory, labor, and law contend, harmonize, and sometimes collide.

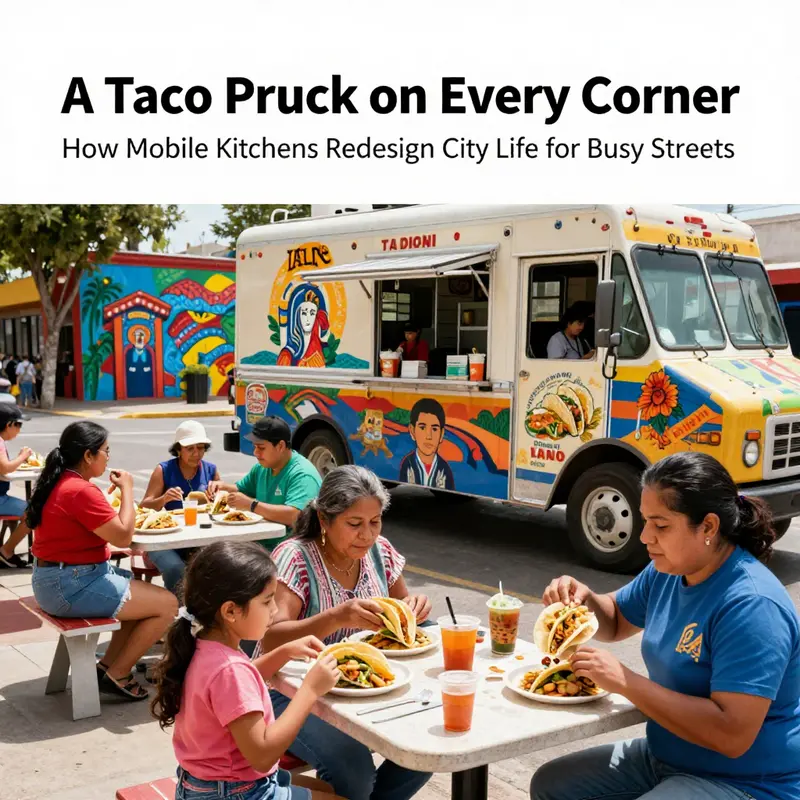

Cultural identity and culinary integration emerge as the central threads that tie the taco truck to broader currents in American urban life. Food from immigrant communities often serves as both a tether to origin and a bridge to a wider audience. The taco truck translates a history of family labor, seasonal risk-taking, and culinary improvisation into a portable, reproducible product that can cross neighborhood lines as easily as a route changes with the wind. When a customer samples a taco that speaks in a dialect of flavors—sun-dried chilies, lime-kissed onions, a hint of herbaceous heat—the experience goes beyond taste. It becomes a small act of recognition: a city acknowledging that heritage is not a relic behind a kitchen door but an ongoing, evolving contribution to public life. The visibility of Latino cuisine in diverse neighborhoods signals a broader social shift—the normalization of immigrant culture as a legitimate, treasured component of a city’s identity rather than an outsider’s spectacle.

At the same time, the taco truck serves as a crucible for community, belonging, and social cohesion. These mobile kitchens are frequently more than places to eat; they are informal gathering spots where workers clock in, families catch up, and neighbors exchange news and recipes. The rhythm of the day—toward sunset, the clatter of cookware, the warm glow of a canopy—creates a temporary public square wherever the truck parks. In this space, cross-generational dialogue can flourish, and cross-cultural exchange becomes a habit rather than an exception. The presence of mobile vendors on city streets can stitch together disparate urban communities through shared meals, a practice that reinforces social networks and sustains informal support systems. In this sense, the taco truck becomes a tiny civic institution, contributing to a sense of belonging even in neighborhoods wrestling with rapid change.

Inclusion and equity in urban policy sit at the heart of the discussion about a taco truck on every corner. The image is not just about serving more food; it is a demand for equitable access to entrepreneurial opportunity and to public space itself. Inclusion involves pathways for immigrant entrepreneurs to participate fully in civic and economic life, including the formal channels that underpin long-term sustainability. Policy approaches should treat cultural heritage as a cornerstone of inclusive city-building rather than as a peripheral anecdote or a festival motif. When city planners and community organizers design spaces for mobile vendors, they are choosing to recognize and facilitate the kind of cultural entrepreneurship that has historically uplifted families and neighborhoods. The goal is not merely more trucks but more levers of opportunity—permits that are transparent and affordable, zones that accommodate the reality of mobility, and programs that connect vendors to entrepreneurship training, health and safety guidance, and financial resources.

Yet this vision encounters systemic challenges that require careful navigation. Regulatory and administrative hurdles—zoning constraints, licensing requirements, and permit processes—often run counter to the needs of small, immigrant-owned mobile food businesses. Health and safety regimes, while essential, can morph into expensive or opaque procedures that disproportionately burden newcomers who lack established networks within city bureaucracy. Economic barriers are equally formidable: start-up costs, working capital, and ongoing operating expenses can overwhelm operators, particularly when access to financing is limited or mistrusted within their communities. Social and political barriers also complicate day-to-day operations. Neighborhood dynamics, bias, and uneven regulatory enforcement can create a climate of uncertainty that undermines stability and long-term planning. These factors intersect with broader structural inequities, reinforcing a pattern in which informal enterprise remains powerful yet precarious, rendering the dream of widespread street food vitality as aspirational as it is practical.

Geographic illustrations in the policy landscape help illuminate both potential and friction. In Los Angeles, for example, the taco truck scene is deeply tied to a large Mexican American community, with trucks woven into neighborhood life and street-level commerce. They act as dynamic venues for social interaction and cultural exchange, illustrating how street-level culinary practice can coexist with formal urban planning goals. In San Diego, collaborative projects and support programs help organize and legitimize mobile vending, linking cultural expression with community development. New York City demonstrates how governance can shape vendor viability through programs designed to balance cultural heritage with urban planning imperatives. Together, these case studies illuminate how cities attempt to harmonize mobility, public health, and equitable access. The broader policy implication is that local governments can play a constructive role by creating accessible permit processes, fair vending zones, and business-support programs that respect cultural practices while safeguarding the public realm.

Balancing regulation with cultural expression requires nuance. The public street should not become a battleground where vendors are shut out of public space or forced into precarious working conditions. Instead, thoughtful policy can foster a supportive ecosystem for immigrant entrepreneurs: multilingual resources, targeted microfinance, and legal assistance that demystifies permitting, health compliance, and business registration. Public space must be conceived as a shared resource with accountability. When communities, vendors, and city agencies co-create vending zones and market-support programs, the results can reflect diverse neighborhood needs, preserve cultural integrity, and promote sustainability. The aim is not to sanitize or standardize cultural expression but to create a framework in which it can flourish—where a taco truck is indeed a mobile thread in the urban tapestry, not a marginal fixture on the edge of traffic.

Ethical and sociocultural insights remind us that the aspiration for a taco truck on every corner speaks to dignity, belonging, and visibility in public life. Food becomes a legitimate vehicle of memory and identity, not a mere commodity to be consumed. The street—traditionally the realm of transit, noise, and pressure—becomes a space where marginalized communities can claim a place, tell their stories, and participate in the civic conversation. This reframing challenges the public to evaluate what we value in our urban landscapes: not only efficiency or aesthetics but also the capacity to acknowledge and celebrate cultural pluralism through everyday acts of sharing a meal. In this light, the taco truck is less a trend and more a symbol of inclusive urban identity—an invitation to see the city as a place where mobility and memory move together.

The concluding synthesis of this chapter emphasizes that widespread taco truck presence is about more than culinary diversity. It embodies a commitment to recognizing and valuing cultural identities within the fabric of daily life. Realizing this vision requires policy frameworks that are culturally informed, regulatorily fair, and oriented toward inclusive economic opportunity. It demands deliberate attention to access, zoning, and support services that help immigrant entrepreneurs thrive without surrendering public space to disorder or fear. As communities continue to advocate for equitable access and recognition, the taco truck remains a potent symbol of cultural richness and the ongoing pursuit of inclusion in public space. The street, then, becomes both stage and classroom—where the lessons of resilience, adaptation, and shared appetite inform how cities grow and how citizens imagine belonging.

For governance context and practical pathways that connect policy with everyday practice, national and local discussions increasingly emphasize accessible permitting, fair vending zones, and community-based support networks. These conversations align with open-access research and urban-planning guidance that highlight how mobile vendors can be integrated into planning frameworks without compromising health, safety, or equity. As cities strive to balance entrepreneurial opportunity with community well-being, the taco truck on every corner stands as a reminder that culture, economy, and space are not separate domains but intertwined facets of urban life. In that sense, the chapter invites readers to imagine not just more food on the street, but more voices at the table of city-building. For further context on how cities regulate and integrate mobile food vendors into urban planning, see the Los Angeles Department of Transportation guidelines. https://www.lacity.org/transportation

Internal link: for discussions on sustainable practices and practical steps that help mobile food vendors operate responsibly within urban systems, readers can explore this resource about sustainable practices for mobile food trucks: Sustainable practices for mobile food trucks.

A Taco Truck on Every Corner: Global Contexts, Policy Tangles, and the Politics of Public Space

The image of a taco truck on every corner has emerged in urban imagination as a playful provocation, yet it also encodes a serious set of questions about how cities shape and are shaped by informal commerce, immigrant entrepreneurship, and the social life of streets. This chapter treats that image as a window into global patterns of mobile food vending, where mobility lowers barriers to entry and local cultures remix culinary repertoires in real time. It is not a blueprint for city design, but a lens to understand how policy, space, and identity intersect in everyday urbanism. Across continents, street food vendors test the edges of regulatory regimes even as they anchor neighborhoods, create gathering points, and contribute to the texture of public life. The taco truck—in its mobility, adaptability, and intimate ties to family and community—becomes a microcosm of broader trends in informal economies, labor mobility, and the struggle to balance economic opportunity with public health, safety, and order.

In many of the world’s metropolises, informal food vending has long operated in a shadow economy that thrives on the margins between permit regimes, health codes, and the unpredictable rhythms of street life. The taco truck movement, in particular, reveals how immigrant communities harness entrepreneurship to transform risk into neighborhood resilience. The mobility of these vendors allows cooks to pursue work in places where fixed storefronts would be prohibitively expensive or inaccessible due to language, capital, or credit constraints. Rather than merely supplying meals, mobile vendors create itinerant social spaces where neighbors gather, share stories, and negotiate competing uses of space. When a truck pulls up at a corner, it is not simply a source of sustenance; it is a signal that a neighborhood is dynamic, adaptable, and capable of absorbing diverse cultural forms into its daily routine. The result is a culinary ecology that travels with the city, revealing how taste becomes a form of urban knowledge, circulated through menus, aromas, and conversations as much as through formal channels of trade.

Yet the same mobility that fuels vibrancy also challenges planners and regulators. Cities must balance access with order, equity with safety, and innovation with accountability. The regulatory architectures that govern mobile vendors vary widely, from permissive regimes that place heavy emphasis on health inspections to more restrictive systems that prize predictability and curbside control. Licensing schemes, health codes, and zoning rules interact in complex ways with street topology, transit corridors, and pedestrian flows. Some cities respond with designated zones or food truck parks, hoping to concentrate activity in areas where parking, waste management, and power supply can be managed efficiently. Others pursue a more distributed model, allowing vendors to circulate through neighborhoods but imposing strict caps on hours, routes, or the number of vendors in a given district. These approaches illustrate a fundamental tension: the desire to democratize access to affordable, culturally resonant food versus the imperative to regulate space in ways that minimize congestion, protect consumers, and maintain neighborhood character. In this sense, public policy becomes a conversation about who gets to use the streets, for how long, and under what conditions the city will be hospitable to informal enterprise.

The urban planning dimension of this conversation is not purely about permits; it is about the quality of space itself. The presence of taco trucks can complicate or enrich the built environment depending on how curb space is allocated, how waste is managed, and how times and places of operation are synchronized with adjacent businesses and transit systems. When planners design soft boundaries for mobile vendors—such as time-limited zones near high-foot-traffic corridors or staggered schedules that reduce overlap with peak traffic—cities can preserve street vitality while mitigating congestion and noise. The literature on food truck regulation and urban planning highlights a similar pattern across cases: well-timed, transparent permitting processes paired with clear safety standards tend to produce more stable vendor ecosystems and greater public trust. In communities where regulation is perceived as opaque or punitive, vendors retreat to informal channels or relocate to less visible sites, often reducing access to affordable meals for lower-income residents and creating tensions between mobile vendors and brick-and-mortar operators who fear unfair competition. The social calculus thus shifts from a simple dichotomy between order and chaos to a more nuanced assessment of how space is valued, shared, and contested in a city’s daily life.

The labor and entrepreneurial dimensions of the taco-truck phenomenon are equally consequential. Mobile vendors are frequently led by immigrant families who leverage low overhead, skill, and networks to build small-scale, service-oriented enterprises. The mobility of the enterprise corresponds to mobility in labor markets: workers may join or leave quickly, bring specialized culinary skills from home countries, and contribute to the multilingual, multicultural texture of urban economies. Even when precise job numbers are contested, scholars consistently point to the role of mobile food vendors in expanding participation in the formal economy, often through entry points that require minimal formal credentials yet demand discipline, hygiene, and customer service excellence. This combination of accessibility and skill formation also supports broader economic inclusion: family members can contribute in flexible roles, and entrepreneurship becomes a pathway for social mobility that complements more traditional employment tracks. However, labor conditions in informal and semi-formal settings can also be precarious. Without scalable, portable compliance, workers may face inconsistent wage regimes, limited access to health benefits, and uneven bargaining power with local authorities and landlords. That tension—between opportunity and security—lies at the heart of governance debates about informal economies.

The economic impact of mobile food vendors extends beyond the sale of meals. Vendors attract foot traffic to commercial districts, stimulate ancillary sales for nearby businesses, and create demand for services ranging from waste collection to portable power supply. In aggregate, the sector can contribute to job creation and local entrepreneurship, particularly in neighborhoods where capital access is constrained. But the same economic flow can be uneven, risking gentrification pressures if popular sites become too valuable or too crowded. Moreover, critics argue that a dense proliferation of mobile vendors can strain public resources, complicate waste management, and complicate enforcement on health and safety grounds. Proponents counter that a well-regulated, vibrant vendor ecology can coexist with established businesses if rules are designed to be transparent, predictable, and equitable. The policy design question becomes not whether taco trucks belong on every corner, but how to orchestrate space, sanitation, licensing, and neighborhood voice so that the benefits are shared rather than captured by a narrow subset of actors.

From a comparative perspective, several regional trajectories illuminate possible futures. In some U.S. cities, officials have experimented with extending permit windows, streamlining health inspections for familiar cooking methods, and creating digital dashboards that track compliance without punishing innovation. In other contexts, regulators have turned to zoning tinkering, creating “food truck corridors” that concentrate activity at transit-connected nodes, public plazas, and night markets. The discourse around these moves often centers on the concept of public space as a commons—a shared resource whose management requires collaboration among residents, business owners, health authorities, and urban designers. When communities co-create rules that recognize cultural significance and economic necessity, the daily practice of eating on the go becomes a form of public pedagogy—an ongoing lesson in how cities can accommodate mobility, diversity, and resilience without surrendering public health or safety.

To translate these ideas into practice, policymakers can draw on a few guiding principles. First, simplify and standardize the licensing landscape so that aspiring vendors can understand requirements without navigating a maze of disparate rules across neighborhoods. Second, pair health and safety standards with technical and financial support—training, refrigeration, waste management, and portable power—so that compliance is realistic and scalable rather than punitive. Third, design flexible space allocation that recognizes peak demand times, seasonal variations, and neighborhood rhythms, allowing spaces to be shared rather than hoarded by a single interest. Fourth, involve community voices in siting decisions, ensuring that residents, local workers, and long-term merchants have a seat at the table when rules are drafted or revised. Fifth, embrace data-informed approaches to monitor traffic, waste, and public health outcomes, while guarding against surveillance that erodes civil liberties or disproportionately burdens marginalized vendors.

In this light, the seemingly whimsical idea of a taco truck on every corner becomes a concrete test case for urban governance: Can cities balance opportunity with order, inclusion with accountability, and culinary diversity with public health? Can a street economy shaped by mobility and family enterprise be integrated into long-term planning without losing its spontaneity and neighborly character? The answer, in many places, is evolving. In some neighborhoods, policy experiments are loosening restrictions and recognizing the social value of vibrant street food ecosystems. In others, tensions persist around curb space, sidewalk use, and the boundaries between formal and informal economies. The shared thread is that creative, well-regulated mobile food ecosystems can contribute to a city’s cultural vitality and economic variety, provided governance mechanisms are transparent, participatory, and oriented toward equitable access. For readers seeking a practical bridge between theory and implementation, the following resource offers a thoughtful examination of how food-truck regulation intersects urban planning and policy design, illustrating core tradeoffs and design choices in real-world settings. Sustainable practices for mobile trucks.

As cities around the world consider how to weave mobility, culture, and commerce into coherent urban strategies, the taco truck remains a provocative, persuasive symbol: a reminder that streets are not merely conduits for movement but stages for expression, entrepreneurship, and shared meals. The challenge is not to banish informality or to romanticize it, but to cultivate a regulatory ecosystem where mobility, safety, and community belonging reinforce one another. The result could be a cityscape in which the aroma of peppers and fish sauce, the clatter of prep stations, and the hum of conversations at a curbside become lasting features of everyday urban life rather than episodic episodes. If policy can architect space that respects both the dynamism of mobile vendors and the rights of residents to clean, safe, and welcoming streets, the corner becomes less a point of contention and more a node of common life. In this sense, the playful phrase about a taco truck on every corner invites serious reflection on how urban futures can be designed to honor culture, commerce, and the intricate choreography of public space.

External reference for further reading on policy frameworks and urban planning considerations: https://www.urban.org/research/report/food-truck-regulation-and-urban-planning.

Final thoughts

Throughout these chapters, the image of a taco truck on every corner evolves from a colorful anecdote into a framework for understanding how cities can blend mobility, culture, and commerce. For urban planners, it offers a case study in public space allocation that respects pedestrian priorities while enabling flexible business models. For entrepreneurs, it demonstrates how low overhead and mobility can seed local wealth and job creation, particularly in immigrant and first-generation communities. Regulators gain insight into designing adaptive zoning and permitting that reduce friction without compromising safety or equity. For communities, mobile street food becomes a platform for inclusion, storytelling, and shared experiences across generations and cultures. The overarching takeaway is clear: when designed thoughtfully, the proliferation of taco trucks can reinforce vibrant, resilient, and accessible city life—without sacrificing order, health, or public space. The street becomes a stage for everyday collaboration, where food, culture, and entrepreneurship combine to create cities that feel human, connected, and alive.